When Ludovic Travers and Superintendent Wharton get a little lost when out for a drive, they end up helping a distressed young lady. She is concerned that her mistress, the actress Mary Legreye has not kept an appointment. Travers and Wharton offer to stop by Legreye’s cottage, but are not prepared for what they find.

When Ludovic Travers and Superintendent Wharton get a little lost when out for a drive, they end up helping a distressed young lady. She is concerned that her mistress, the actress Mary Legreye has not kept an appointment. Travers and Wharton offer to stop by Legreye’s cottage, but are not prepared for what they find.

Mary’s handyman and Mary herself are both dead, poisoned, poison which was apparently self-administered. But why was Mary found sitting upright in a throne-like chair, mimicking her most famous role as Mary Tudor? With no real evidence other than a suspicion, is it possible that it was simply an odd case of suicide? Or was it a cunning murderer who looks like they are going to get away with it?

Christopher Bush was… well, another author like Brian Flynn who escaped getting mentioned in Twentieth Century Crime and Mystery Writers – seriously, it’s a great book for those who get a mention, but there are some serious gaps in it. But Bush is pretty obscure, despite writing over fifty books (including the wonderfully titled The Case Of The Flying Ass). He’s lacking a Wikipedia page, but there is a reference on gadetection here. According to the back of this one, his books were published in America and in “every European country outside the Iron Curtain”. Which is nice.

I have to thank my Secret Santa for this one – the first of six Green Penguins – and I can’t help but think it was chosen with the title, given my bent for Historical Crime Fiction, despite this not being an historical. And while I appreciate the chance to experience yet another obscure Golden Age crime writer, I can’t avoid the fact that this one is a bit on the crap side.

Why? Well, it’s very talky with Travers and Wharton, both of whom hardly light up the page, spending a lot of time debating whether there is really a case to investigate or not and then checking and re-checking alibis. It’s a bit of a railway-timetable-esque tale with it taking an age for the murderer to finally give themselves away. It also doesn’t help that the suspects are as dull as dishwater, and despite one really clever idea – namely why Mary is found posed on a throne – it’s not enough to save this one.

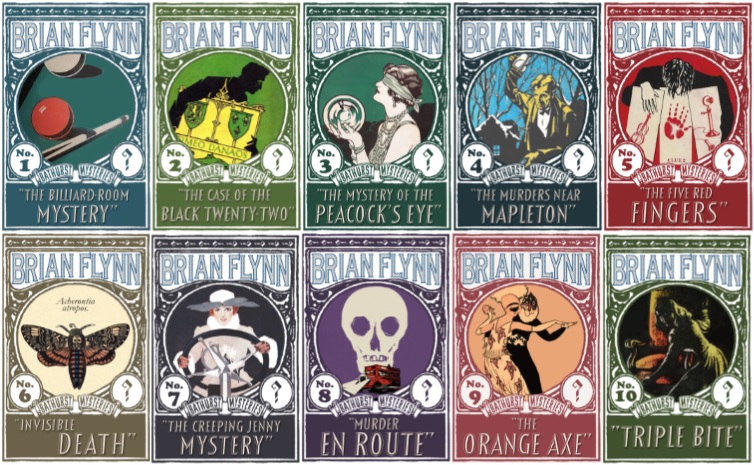

So, a disappointment to be honest. Unlike Brian Flynn, who’s Mystery Of The Peacock’s Eye I couldn’t put down, there were times where I had trouble picking this one up. So one less author to obsess over… Oh, this one isn’t recommended, btw…

I had never heard of Christopher Bush until now, but I am very familiar with 20th Century Crime and Mystery Writers, and own both the 3rd and 4th editions of it. (I also had the 2nd but gave it to a friend.) Bush is listed and written about in both the editions I have. The books are treasures. But, yes, writers were added and dropped from one edition to the next. Curious which edition you have?

LikeLike

Yes, I have the first edition and even here Christopher Bush is listed and written about.

LikeLike

Miles BURTON, Roger BUSBY, Gwendoline BUTLER…, nope, no Bush in the second edition…

LikeLike

Mine’s the second edition. Probably why it was so cheap…

LikeLike

Rather strange. I have the first edition (1980) published by the Macmillan Press. Here Christopher Bush is listed between Roger Busby and Gwendoline Butler.

LikeLike

(continuing)

In addition to the list of books, the following facts are mentioned about Christopher Bush:

BUSH, Christopher. Pseudonym for Charlie Christmas Bush; also wrote as Michael

Home. British. Born in East Anglia, in 1888( ?): birth date unrecorded. Educated at

Thetford Grammar School, Norfolk; King’s College, London, B.A. (honours) in modern

languages. Served in both world wars: Major. Schoolmaster before becoming a full-time

writer. Died 21 September 1973.

Christopher Bush, during his 40-year writing career, produced over 80 books. His leisurely

English is easy to read; within their limits – and he wrote very much to a pattern – his novels

satisfy because the puzzle is clever, the story not stereotyped. Essentially they are alibi stories,

but their complexity is often more ingenious than Crofts’s. They nearly always fall into three

parts, sometimes with a prologue: always the crime, generally murder, is followed by the

investigation, which results in a long pause, with a number of well-alibied suspects; the third

part generally follows after a gap of some months, when some fortuitous incident starts a

new train of thoughts or suggests an inconsistency in earlier evidence.

Of course there are maps and plans, an essential of his period of writing. He had the best of

both worlds with his detective. Ludovic (Kim) Travers, part-owner of a detective agency, is

also a nephew of the Commissioner for Scotland Yard, thus providing a useful link with

Superintendent Wharton. Travers and Wharton work happily together, with neither

concealing much from the other, and Wharton often using Travers as a stalking horse in the

last stages of the case, though often Travers has the break-through idea.

The Perfect Murder Case does not quite live up to its dramatic beginning but has an

ingenious alibi. The Case of the Dead Shepherd and The Case of the Treble Twist are tricky.

Even his last, The Case of the Prodigal Daughter, very up-to-date with Soho vice, is well-

constructed, though not as complex as those of his middle and war periods. From earlier

days, the best are The Case of the Burnt Bohemian, The Case of the Seven Bells, and The Case

of the Murdered Major.

LikeLike

Thanks for the info, Santosh. Utterly baffled at Bush’s absence from volume 2. Does your copy mention Brian Flynn?

LikeLike

No.

LikeLike

Refer http://gadetection.pbworks.com/w/page/7932381/Twentieth%20Century%20Crime%20and%20Mystery%20Writers

where it is mentioned that some authors were added and some removed in the second edition and “because of the removed material this edition(second) cannot fully replace the previous one, but it is worth having for the new and corrected entries.”

It seems that in the third edition, the authors removed from the second edition were added back.

LikeLike

Looks like I bought the wrong edition – at least I got it for an absolute bargain…

LikeLike

I’ve been wondering whether or not to try his work but I think you have solved that issue for me!

LikeLike

Thanks for this. A ‘railway-timetable-esque tale’ is the best description for a boring/drawn out mystery novel I have heard for ages.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Did I read that right? He used Christopher as a pen name because his real given names were *Charlie Christmas*?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, that is right !

LikeLike

“He’s lacking a Wikipedia page…..”

Well, he is available in French Wikipedia !

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christopher_Bush

He was born on 25th December; this will explain his name !

LikeLike

[…] The Case Of The Tudor Queen by Christopher Bush […]

LikeLike

[…] is my second encounter with the work of Christopher Bush, the first being The Case Of The Tudor Queen, which I was a bit underwhelmed by. But now Dean Street Press are on the case and are re-publishing […]

LikeLike

[…] far my encounters with Christopher Bush and Ludovic Travers have consisted of The Case Of The Tudor Queen (so-so) and Dancing Death (good, but I wasn’t as blown away by it as some people). This one was […]

LikeLike

[…] author where I was less enamoured by my first encounter – in this case The Case Of The Tudor Queen – but this one completely won me over. A clever mystery – a bit guessable, yes, but clever […]

LikeLike

[…] tree to make life easier for themselves. So stuff that for a packet of biscuits. And I’ve read The Case Of The Tudor Queen before, so it’s on to Book 19, i.e. this […]

LikeLike