Vernon House, home of Sir Eustace Vernon, and Christmas is in full swing. His nearest and dearest, and the great and the good of Mapleton, are in attendance… you can tell things didn’t go as planned. Before the night is out, Sir Eustace has disappeared and his butler, Purvis, lies dead, poisoned, with a threatening message inside a red bonbon in his pocket. Oh, and the butler seems to be missing one or two things that might be expected – it seems that Purvis was actually a woman, something that nobody seemed to be aware of.

Vernon House, home of Sir Eustace Vernon, and Christmas is in full swing. His nearest and dearest, and the great and the good of Mapleton, are in attendance… you can tell things didn’t go as planned. Before the night is out, Sir Eustace has disappeared and his butler, Purvis, lies dead, poisoned, with a threatening message inside a red bonbon in his pocket. Oh, and the butler seems to be missing one or two things that might be expected – it seems that Purvis was actually a woman, something that nobody seemed to be aware of.

Meanwhile, despite it being Christmas Eve night, police commissioner Sir Austin Kemble and sometime investigator Anthony Bathurst are out for a drive when they come across an abandoned car at a railway crossing. Looking around, they find a body that seems to have been hit by a train. The body of Sir Eustace Vernon, with two rather interesting properties. One, a bullet hole in the back of his head. Two, a red bonbon in his pocket with a threatening message in it…

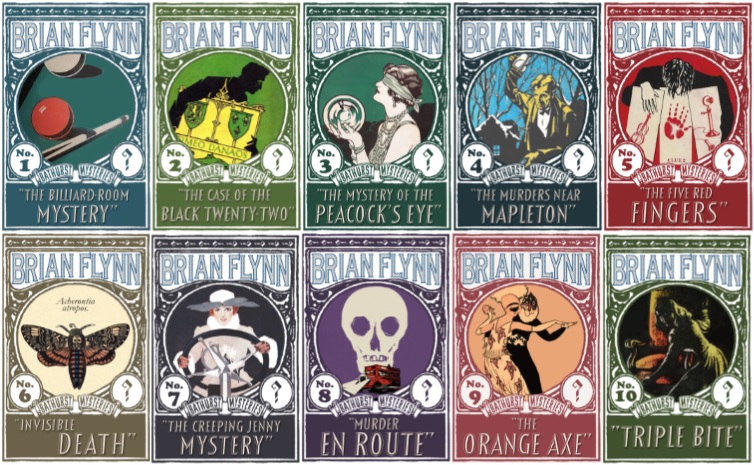

The fourth Anthony Bathurst mystery, following The Billiard Room Mystery, The Case Of The Black Twenty Two and The Mystery Of The Peacock’s Eye, comes from 1929, the same year as the only other GA example of the wrong-gender-corpse that I’m aware of, namely Gladys Mitchell’s debut Speedy Death. There’s a Josephine Tey book from about twenty five years later, but other than that, nothing that I know of. Was there such a real-life murder in the twenties that inspired both books? I can’t believe that there was enough time for one author to pinch the idea from the other (and if that was the case, Mitchell must have pinched it given that Flynn cranked out two more books in the same year). But to be honest, it’s a pretty minimal part of the plot.

OK, it’s pretty clear by now that I’m a big fan of the long-lost Brian Flynn, author of approximately fifty mystery novels between 1927 and 1958, almost all featuring sleuth Anthony Bathurst, a character that Flynn seemed determined to keep somewhat nebulous. To establish what we learn about Bathurst in this book:

- He’s solved a few crimes before but doesn’t want to solve too many – “I get sick of a surfeit of cases. One every now and then does me very well”

- He went to Oxford University, in particular being a member of OUDS, the Drama Society

- He can be a little verbose on occasions, seemingly in this case when talking to the “working classes” – he even, for no particularly good reason, calls one Albert Fish “Alberto Poissonio”

- He’s good looking enough for a barmaid to give him the nickname “Angel Face”

- He drives a Crossley

- He doesn’t consider himself a gentleman

- He considers “your blasted cleverness is inhuman” to be quite a testimonial to his prowess

- He has some pretty negative views on marriage – to be specific would be a spoiler though…

And that’s it, apart from a tendency not to get on with local bobby Inspector Craig. At one point, Kemble mentions that if Bathurst wasn’t there, he would have called in Inspector MacMorran, the police inspector who will go on to be the long-running supporting sleuth in the series, but hasn’t, I don’t think, made an appearance to date. In common with the other books that I’ve read, there’s no real background to Bathurst, but he’s a charming lead, all the same, leading the reader down the path to the solution to the mystery – which I think is fairly clued, although some info comes quite late in the day.

It’s a complex tale but very readable – something I think is one of Flynn’s strengths. One of the highest complements that I can pay is that as the solution was slowly revealed, I put the book down between chapters to have a bit of a think about things. There is quite a lot to puzzle out here but it all ties together nicely at the end of the day, letting the reader work out bits and pieces – or not, as the case may be…

You could make a case that the investigation is a bit odd – there never seems to be any real curiosity about Purvis, the mysterious female butler, leaving the reader to have to guess their involvement in the big picture until it is revealed, almost as a matter of fact – so it’s best that you don’t think too hard about the reality of the situation, which is probably a good thing, as realism doesn’t really come close to this tale. Which is definitely not a criticism, just to be clear…

A quick diversion into the signs of the times from this one:

- The existence of such a thing as a village coffee-stall – the pre-cursor to Starbucks

- The use of the phrase “one pound currency notes” – what other sort of pound notes were there?

- The phrase “Na-poo!” which means “nothing doing, by the way”

- A pub with the glorious name of “The Cauliflower and Crumpet”

So, another piece of evidence in the case of why Brian Flynn should be reprinted as soon as possible. A well-crafted mystery that keeps the reader’s attention while sticking to the classic whodunit structure. Sure, it’s not in the same league as Dame Agatha, but it’s a damn sign finer than anything by Dame Ngaio. Fingers crossed it’ll be available at some point in the future…

For a second opinion – the first time I can say that for Flynn – do pop over to see what Curtis Evans had to say. But from me, at least, this is Highly Recommended.

This is the only Brian Flynn book which I have read but it was very good and I will be reading more. It was from this volume that I gleaned the marvellous word “fascinorous” which, although obsolete, I have every intention of bringing back by using it at every opportunity.

LikeLike

Good luck hunting down other titles. I’ve yet to find one that I dislike, but the earlier ones are a bit more imaginative. There’s a bibliography page of my reviews to date in the tabs.

LikeLike

There are at least three more of Flynn’s books available at Hathi Digital Trust which was also my source for this novel. I have a limited budget for hardcopy books so I may be limited to those in the immediate future but I am always looking for books and do occasionally find a cheap copy of something worthwhile in the way of GAD authors. Flynn certainly qualifies as worthwhile in my view.

LikeLike

I’ve got the three other titles – the Spiked Lion seems to be a dodgy pdf of the copy here – but have only read The Billiard Room Mystery so far, which is not his finest work but interesting for all sorts of reasons. Don’t read my review of it though as I probably hint too much at something, in hindsight…

LikeLike

The woman in butler drag reveal was what reminded me of Speedy Death, but I thought that was enough of a spoiler not to mention. Judgment call! It is odd though, that that rather queer detail would pop up in two books in the same year.

LikeLike

I figured both happened so early on that it was fine to mention it, in part because of the curiosity of it. Someone did mention to me a possible real-life case that may have inspired it but I’ll be jiggered if I can find the comment now…

LikeLike

[…] of The Billiard Room Mystery (Flynn’s slightly flawed but enjoyable debut), the excellent The Murders Near Mapleton and The Crime At The Crossways, one that I’ve got but not read […]

LikeLike

[…] his fourth outing, The Murders Near Mapleton, Bathurst has become friends with Sir Austin Kemble, the Commissioner of Scotland Yard, friendly […]

LikeLike

[…] Of The Black Twenty-Two and the genuine long-lost classics The Mystery Of The Peacock’s Eye and The Murders Near Mapleton. I’ve been putting this one off for a while, reading some of his later output first, as I figured […]

LikeLike

You ask rhetorically “Are there any other types of currency notes in the UK beside one pound?”

The answer is yes indeed.

I grew up in London and as a child if an uncle gave you a pound note during the war that was a huge treat but if someone got a fiver or tenner that was better yet. If you read Michael Arlen’s “Too Early Seen Unknown” he explains what a five pound note could do in the way of shopping at that time.

There were higher denominations too, twenty pounds and fifty pounds. I never saw one for a hundred pounds but believe it existed.

LikeLike

Just to clarify – my question meant what other sort of pound notes were there apart from notes used for currency. I’m well aware that there are/were other denominations.

Of course, these days one doesn’t appreciate the value of one pound. Even in my youth, which was nowhere near the late twenties, it was a lot of money. How things change…

LikeLike

As far as I know the only currency notes were for pounds sterling. There was the guinea but it did not have its own note. A few gold sovereigns still circulated when I was very young but the Bank of England called them all in.

LikeLike

PS See “The Owl and the Pussy Cat” by Edward Lear.

“They took some money and plenty of honey

All wrapped in a five pound note”.

LikeLike

[…] also: The Puzzle Doctor, Curtis Evans and TomCat have also reviewed this […]

LikeLike

[…] Steve Barge @ In Seach of the Classic Crime Mystery: ‘A well-crafted mystery that keeps the reader’s attention while sticking to the classic whodunit structure. Sure, it’s not in the same league as Dame Agatha, but it’s a damn sign finer than anything by Dame Ngaio.’ […]

LikeLike

[…] Murders near Mapleton has been reviewed, among others, at The Passing Tramp, In Search of the Classic Mystery Novel, Beneath the Stains of Time, Cross-Examining Crime, Bedford Bookshelf, Mysteries Ahoy! and […]

LikeLike

This has a very twisty and clever plot. I thought the question of why didn’t a character ride in the car was a great clue, and it was fairly presented early on for the reader to ponder.

LikeLike