“Inasmuch as I was a member of the audience tonight at a private theatrical performance and Anthony Bathurst was playing lead for the company (amateur of course) that was entertaining us, I had no opportunity for conversation with him, but I am certain that had I had this opportunity, I should have found that his brain had lost none of its cunning and that his uncanny gifts for deduction, inference and intuition, were unimpaired. These powers allied to a masterly memory for detail and in an unusual athleticism of body, separated him from the majority – wherever he was, he always counted – he was a personality always and everywhere. A tall, lithe body with that poised balance of movement that betrays the able player of all ball games, his clean-cut, clean-shaven face carried a mobile, sensitive mouth and grey eyes. Remarkable eyes that seemed to apprehend and absorb at a sweep every detail about you that was worth apprehending. A man’s man, and, at the same time, a ladies’ man. For when he chose, he was hard to resist, I assure you.”

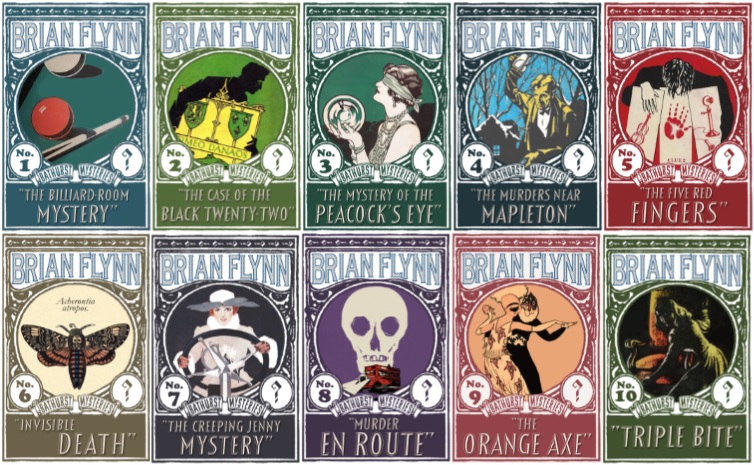

The Billiard Room Mystery, Brian Flynn (1927)

This month, the Tuesday Night Bloggers, a ragtag group of ne’er-do-well crime fiction bloggers, to which I’m an occasional contributor, are discussing the Great Detectives of Fiction. One of us has recently contributed to a book on the 100 Greatest Detectives but such a list will always have some omissions – we’re going to address that. I’m going to start off with someone who ought to be in the pantheon of Great Detectives but for whatever reason has been lost to time – Anthony Lotherington Bathurst.

This month, the Tuesday Night Bloggers, a ragtag group of ne’er-do-well crime fiction bloggers, to which I’m an occasional contributor, are discussing the Great Detectives of Fiction. One of us has recently contributed to a book on the 100 Greatest Detectives but such a list will always have some omissions – we’re going to address that. I’m going to start off with someone who ought to be in the pantheon of Great Detectives but for whatever reason has been lost to time – Anthony Lotherington Bathurst.

Bathurst is the series sleuth of Brian Flynn, featuring in, as far as I’m aware, all but one of his 54 mystery novels – I believe that he’s not in Tragedy At Trinket, although I could be mistaken. One of the issues with Flynn is that his books aren’t just hard to find but in some cases they seem not to exist. After a year’s determined searching, I’ve picked up copies of 21 of them, and there are a few more titles that are a bit out of my price range, but there are at least twenty titles that I have never seen for sale at any price. Hence I’m working on a sample of his work and extrapolating somewhat.

I’ve been lucky enough to have been sent a couple of articles written by Flynn, but he only addresses Bathurst briefly, saying that he endeavoured to create Bathurst in “the true Holmes tradition”. So with little help from the author, what do we know of Bathurst?

Well, apart from the opening description from an old school friend, there are a few facts to be gleaned from his earlier appearances. He is of Irish descent but as he asks the person who puts that to him (in The Spiked Lion) how he knows, we can presume that he has no accent. He went to Uppingham School, a prestigious private school in Rutland, which features Stephen Fry, Mark Haddon and Boris Karloff among its alumni. He then went to Oxford – college unknown – where he participated in multiple sports, although cricket is his true love, and was a member of OUDS, the Oxford University Dramatic Society. Bathurst does make an odd comment about his past in OUDS in Tread Softly:

“I met a girl there [OUDS]. Glad I didn’t marry her because I’m inclined to dream myself on alternative Mondays. A man never knows his luck, does he?”

Not entirely sure what he’s getting at there, to be honest…

Then we have an indeterminate amount of time unaccounted for, as I don’t seem to have a handle on his age. It would seem from the description above – from 1927 – that he’s middle-aged or younger, but I’ve yet to encounter any description of Bathurst fighting in the war. As Oxford was running a minimal ship during the war years, and he talks of someone being three years ahead of him at university, that would perhaps make him 18 in 1921. If you do the sums, that makes him 24 for The Billiard Room Mystery, which is possible, but he does seem older than that. Nobody calls him too young or doesn’t take him seriously for example. There is of course the possibility, nay likelihood, that Flynn chose simply not to mention the war – it’s notable that in 1942’s Reverse The Charges, there is no mention of the war currently raging…

Then we have an indeterminate amount of time unaccounted for, as I don’t seem to have a handle on his age. It would seem from the description above – from 1927 – that he’s middle-aged or younger, but I’ve yet to encounter any description of Bathurst fighting in the war. As Oxford was running a minimal ship during the war years, and he talks of someone being three years ahead of him at university, that would perhaps make him 18 in 1921. If you do the sums, that makes him 24 for The Billiard Room Mystery, which is possible, but he does seem older than that. Nobody calls him too young or doesn’t take him seriously for example. There is of course the possibility, nay likelihood, that Flynn chose simply not to mention the war – it’s notable that in 1942’s Reverse The Charges, there is no mention of the war currently raging…

Given his background, and the lack of any mention of a career, we can probably assume Bathurst is living off an inheritance or a trust fund. There’s no mention of his parents that I’ve seen. But he’s also not a professional detective.

“Bathurst never took his ‘Varsity cricket seriously enough. Had he done so he would probably have skippered England – he’s the kind that distinguishes whatever he sets his hand to.”

In the Billiard Room Mystery, his first appearance from 1927, he assists Inspector Baddeley in bringing the murderer to justice. It’s a country house mystery, where a guest is both strangled and stabbed, and Bathurst is already present as a guest, so he isn’t recruited to solve the crime. Rather, once the police are on the scene, he takes his host to one side:

“I’ve always been attracted by the affairs of this nature, sir, little thinking that one day I should be swept into one. Would you be good enough to give me carte blanche as it were, to do a little investigation off my own bat? With your authority, you see, acting in a private capacity as your agent, I can satisfy Inspector Baddeley of my bona fides if he catches me nosing into things.”

Hence it can be safely said that The Billiard Room Mystery is Bathurst’s first case.

His next outing is in The Case Of The Black Twenty-Two, when his help is enlisted by Peter Daventry, a lawyer up to his neck in trouble with a case of simultaneous identical murders, but more importantly, the brother of Gerry Daventry, a bit player from the previous book. He is alongside a new police inspector, Inspector Goodall, who accepts his help due to the same rationale as in the previous case – he’s been asked to help by someone important, so fair enough. Bathurst’s musings seem to say that he hasn’t had anything of interest to do since the previous book.

For his third outing, The Mystery Of The Peacock’s Eye, Bathurst is approached by the Crown Prince of Clorania to sort out a little blackmail problem that, shall we say, snowballs into murder and mayhem. It isn’t revealed how the Prince knows Bathurst – when contemplating the letter arranging the appointment, the only referees he considers are the aforementioned Goodall and Baddeley – but Bathurst does reveal that he is not a private investigator (almost immediately after saying that he will “take the case”).

For his third outing, The Mystery Of The Peacock’s Eye, Bathurst is approached by the Crown Prince of Clorania to sort out a little blackmail problem that, shall we say, snowballs into murder and mayhem. It isn’t revealed how the Prince knows Bathurst – when contemplating the letter arranging the appointment, the only referees he considers are the aforementioned Goodall and Baddeley – but Bathurst does reveal that he is not a private investigator (almost immediately after saying that he will “take the case”).

By his fourth outing, The Murders Near Mapleton, Bathurst has become friends with Sir Austin Kemble, the Commissioner of Scotland Yard, friendly enough to be out for a Christmas Eve drive. When they discover a body that has been both hit by a train and shot – Flynn does like his double murder methods – Bathurst naturally gets involved. By now, he seems to be considering himself an actual detective, but doesn’t take on too many cases. When asked by Kemble if he has a current case, he replies: “I get sick of a surfeit of cases. One every now and then does me very well.”

Bathurst can be a bit full of himself – calling a character who he has just met Alberto Poissonio (his name is Albert Fish) just reeks of arrogance and makes you want to smack him – but his charm helps him get by, both with the other characters and the reader.

By Invisible Death, Bathurst has a reputation and not just of being someone who is “trained to a hair, hard as a bag of nails and without an ounce of superfluous flesh, an eminently useful man in most places”. Bathurst is summoned to a country house once again due to a recommendation from someone from a previous case, but when the villains of the piece get wind of the cry for help, they do whatever necessary to stop him from getting there, so they’ve clearly heard of him. Bathurst needs to recruit old chum Peter Daventry to help him get to the scene of the crime (Daventry seems to have become a bit of an oddly verbose hard-man since The Black Twenty-Two).

Jumping ahead a few books, and we come to The Spiked Lion and by this point Bathurst is such a great detective that Sir Austin has him on the 1930s version of speed-dial whenever a case of interest comes up. Either that or he knows how thick the members of his own police force are, although it has to be said that anyone who could put two and two together to complete unwrap that mystery should be promoted to the top job. Indeed, Inspector MacMorran, who will go on to be Bathurst’s regular sidekick, is a mostly superfluous character here.

Jumping ahead six or seven more cases, we come to Tread Softly, which opens with Chief Inspector MacMorran (he’s been promoted) asking Bathurst directly for help. They seem on friendlier terms and MacMorran is taking a much more active role, although isn’t too impressed when Bathurst can’t decide if he agrees with MacMorran’s theory. Bathurst is similarly recruited in Reverse The Charges – MacMorran, when being given the case is referred to as “immediately” calling in Bathurst, either in recognition of Bathurst’s powers of deduction or his own lack of them. Both these titles are lacking in any background for Bathurst though, presenting him as if the reader will just accept him as being “the detective”.

Jumping ahead six or seven more cases, we come to Tread Softly, which opens with Chief Inspector MacMorran (he’s been promoted) asking Bathurst directly for help. They seem on friendlier terms and MacMorran is taking a much more active role, although isn’t too impressed when Bathurst can’t decide if he agrees with MacMorran’s theory. Bathurst is similarly recruited in Reverse The Charges – MacMorran, when being given the case is referred to as “immediately” calling in Bathurst, either in recognition of Bathurst’s powers of deduction or his own lack of them. Both these titles are lacking in any background for Bathurst though, presenting him as if the reader will just accept him as being “the detective”.

As the series progresses, hints to Bathurst’s background are still few and far between. In The Case Of Elymas The Sorceror (1945), Bathurst is suffering from Muscular Rheumatism, but as that’s a generic term of the time for a multitude of ailments, that doesn’t help us pin down his age.

In Exit, Sir John and The Sharp Quillet, we meet Helen Repton, a female member of Scotland Yard who has something of a flirty relationship with Bathurst. To be honest, I need to read more of the books from this time, but I don’t think it goes any further than that, although this seems to be the most interest Bathurst ever shows in a woman. She returns in a number of the later books, one of the earlier examples of a woman at Scotland Yard, I believe.

In Exit, Sir John and The Sharp Quillet, we meet Helen Repton, a female member of Scotland Yard who has something of a flirty relationship with Bathurst. To be honest, I need to read more of the books from this time, but I don’t think it goes any further than that, although this seems to be the most interest Bathurst ever shows in a woman. She returns in a number of the later books, one of the earlier examples of a woman at Scotland Yard, I believe.

So what is it about Bathurst that places him amongst the ranks of the Great Detectives? Well, he’s fun to be around, he solves some of the most convoluted cases (seriously, take a look at The Spiked Lion) while never losing the reader with his explanations – while the plots he solves are complex and can be far-fetched, the reader never feels lost as to what’s going on, at least once Bathurst reveals all. He’s willing to share his thoughts with his fellow sleuths (and the reader) more than some sleuths and he has a sense of humour (although a few of his jokes are somewhat intellectual and over my head). If any “lost series” needs to be found again, it’s this one, so you all can appreciate the genius of Anthony Lothering Bathurst.

“Bathurst? I think I’m beginning to understand. Are you the Anthony Bathurst that messes round with…” “Guilty, sir. The messing around is admitted. And now that we all know each other, everything’s fine and dandy.”

And Cauldron Bubble, Brian Flynn (1951)

Shouldn’t the date for “And Cauldron Bubble” be 1951?

LikeLike

Great start to the TNB posts! Very useful to have such a overview, though it is a shame that Flynn says so little about his own creation. Would you say Bathurst is part of or a variation on the Sheringham/Campion etc. school of sleuths? And I was also wondering if other GAD writers mention him at all? It is a pity that Sayers is rather concise in her comments when she reviewed two of Flynn’s novels, focusing more on his language than his sleuth – though I think she too comments on the Holmes connection.

LikeLike

Flynn might have said more, but not in the two interviews that I’ve been sent. I’ll post more on them in a later post on Flynn himself.

As to the school that Bathurst belongs to, Campion, to the best of my knowledge, is probably the closest. Some of the stories do veer towards conspiracy style plots, but never veering away from the central whodunit notion.

All I’ve got in terms of writing on Flynn is the two Sayers reviews, two NY Times reviews (one praiseworthy, one absolutely scathing) and those few from the Saturday Review of Books, which can be called, at best, concise. Remember this is an author that Martin Edwards hadn’t heard of, so there can’t be much out there. He wasn’t a member of the Detection Club but no idea why. But as I’ve said before, the books as clever and fun to read which to be honest, is unlike some who have survived the purge… I’m still on the hunt for more on Flynn and his background. More soon, hopefully…

LikeLike

Based on your overview I did think there might be some crossover between Campion and Bathurst, though as you say it is weird/odd how absent Flynn’s work is from in terms of material written about it. Sounds like you’re doing a great job tracking down this material though, sparse as it is. Have you tried looking in the British Newspaper Archive online for stuff?

LikeLike

My good lady wife has a subscription. A quick hunt for The Spiked Lion reveals one praiseworthy review. I’ll keep hunting…

LikeLike

Fingers crossed there are more reviews/references to come.

LikeLike

[…] site, as well as Noah Stewart‘s site, Moira’s Clothes in Books, and the Puzzle Doctor’s In Search of the Classic Mystery every Tuesday in April, you will have a good […]

LikeLike

[…] up this week, Puzzle Doctor brought us yet more enticing words on the subject of Anthony Lotherington Bathurst, sleuth in the novels of Brian Flynn which the Doc is tearing through much to the interest of GAD […]

LikeLike

Part of the problem have may have been his publishers. The DC could be lax about these things, as I talk about in Was Corinne’s Murder Clued? They didn’t even like having to buy books to review for determining admission of prospective members.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love this: I have been reading GA crime stories for more than 40 years, hovering up old paperbacks, and I had never heard of author or sleuth till very recently. When you asked if anyone else had grabbed him for this meme, I felt like replying ‘no-one but you has even heard of him’, but obviously that is unfair, from the comments above. But still, if you had posted on April 1st I might have started to wonder. (Inventing a lost GA author – that’s a good idea!)

Anyway – a most enjoyable roundup, and I am very glad to know more about this lost hero!

LikeLiked by 1 person

To be fair, Moira, the comments above are from people who heard of him since my obsession began a year or so ago, started from a chance Christmas present from my sister-in-law, who wandered into a second hand bookshop, and asked for suggestions. I’ve no idea how much that copy of The Mystery Of The Peacock’s Eye cost, but to me, it’s priceless.

I am hopeful that Flynn may see a reprint at some point – you see, his books are a lot more fun than some other rediscovered authors out there…

LikeLike

I keep hoping I’ll come across one of Flynn’s books. No luck yet. But you keep making me want to read them.

LikeLike

I’m currently reading one of the impossible crime mysteries Flynn wrote – MURDER EN ROUTE (1930), his eighth book according to his bibliography. I’ve found out a lot about Bathurst in two paragraphs that make him sound like a Philo Vance style detective — ludicrously erudite on multiple topics, filled with knowledge on esoterica and arcane intellectual topics. It’s almost like a parody, IMO. I never noticed this before in other Bathurst books, but I read those other mysteries more than ten years ago and I never did finish LADDER OF DEATH as I mentioned.

This time I’m reading closely and taking notes, writing down page numbers and marking passages to quote so as to fill in gaps and give you a fuller “biography” of your hero. Luckily, this time the bizarre plot is keeping me engaged and intrigued. (But I can barely endure Flynn’s verbose and redundant prose style.) In MURDER EN ROUTE a strangling takes place on the upper level of a doubledecker bus with no one having gone up or down except for the one passenger who was killed. I’m hopeful that Flynn will manage to pull off something impressive and not something absurd.

LikeLike

Murder En Route is the earliest title that I don’t have so do be careful with spoilers, but many thanks for this, John. Typical that the title that I don’t have is the one that fleshes out the character a bit (although it’s only a the Spiked Lion where I made notes as I read it). I know what you mean about Flynn’s writing style but I rather enjoy it (obviously). Sayers made a similar comment in one of her reviews of his work. Hope you enjoy this one.

LikeLike

Oh yes, spoilers. […sigh…] Most people consider my reviews to be full of spoilers, but I don’t. Nevertheless, I’ll be restraining the side of me that tends to go into great detail about the plot and characters. I will only discuss the bare bones of this very involved plot. The rest of the book has so much more to discuss. It’s absolutely fascinating actually. Especially three instances that prove Flynn was clearly influenced by a popular writer of the Edwardian era. At least when he wrote this one. I have a feeling the influence shows up elsewhere in his work.

In reading MURDER EN ROUTE I’m reminded of my reading experience with A. Fielding’s TRAGEDY AT BEECHCROFT — expected a middling story and got something mindboggling complex. Flynn’s plot is not as complex as Fielding’s mystery, but it’s not at all middling either. More importantly, Flynn’s clueing is rather amazing and abundant. I’ll stop there or I’ll end up writing my post in these comment boxes. I’m just glad that I choose a very good book to reintroduce myself to Bathurst.

LikeLike

Massively jealous, John, as there isn’t a single copy of this one out there that I can see… Now I know how my readers feel when I do a Flynn review.

LikeLike

There is one at Biblio at 25 dollars plus shipping.

https://www.biblio.com/book/murder-route-flynn-brian/d/995987881

LikeLike

Thanks but the shipping puts it well out of my price range… 😞

LikeLike

[…] never have made the list – Adrian Monk and Velma Dinkley (and friends) for obvious reasons and Anthony Bathurst for reasons of decades of neglect from uncaring crime fiction fans. Today though, I’m going to […]

LikeLike