When Dr Sanders was asked by Marcia Blystone to see if her father was all right, he never expected what would happen next. Entering the flat on Great Russell Street, he finds all four party guests, all poisoned with atropine. Three of them are fighting for their lives, but the fourth, the host Felix Haye, is beyond help – he has been stabbed through the heart. As the remaining three recover, they are all confident of one thing. There was absolutely no way that the drinks, the only thing they consumed, could have been poisoned.

Felix Haye collected criminals – thieves, arsonists, murderers – and kept the evidence at his solicitors, sealed in five boxes. On the same night as the tragedy at his flat, however, the boxes were stolen. With the mysteries deepening, and a second murder to contend with, Superintendent Masters and Sir Henry Merrivale find themselves up against a cunning – and desperate – murderer.

“I’m the old man. You trust me and everything will be all right, in spite of what Masters tells you.”

John Dickson Carr (aka Carter Dickson) published four novels in 1938. One, To Wake The Dead, is perfectly fine, but is never mentioned in the same breath as his best work. Two more, The Crooked Hinge and The Judas Window, are usually, wrongly and rightly respectively, cited in his top ten works. However Death In Five Boxes is often overlooked and rarely gets a mention.

The reason for this may well be the impossibility of the crime, which was probably more miraculous in 1938. The thing necessary to achieve the effect was rare in 1938, unlike today, so I think it’s much more guessable for the modern reader. However writing this book off for that element is a mistake, as this is a magnificent mystery.

John Dickson Carr was renowned for his locked rooms and impossible crimes, but that wasn’t his only talent in crime writing. I’ve been musing on this for a while, and I have a simple question. Was there any author who was better at hiding the villain than him? I’ve mentioned this before when I reviewed Til Death Us Do Part, but Carr doesn’t go for the least likely suspect approach. He has a number of tricks up his sleeve, but the net result is to make the reader overlook the murderer as a viable villain, despite piling the clues high for the reader to completely miss.

This is a fantastic example of this. You can see this as possibly a response to Christie’s Cards On The Table, with a very closed circle of suspects, assembled because of their villainy, one of whom murders the host who has a hold over them. This takes the story in an entirely different direction, with Carr filling the tale with multiple misdirections to baffle and bamboozle the reader, while still taking the time to flesh out the suspects in a sympathetic manner.

Cynical readers might take issue with the number of times Merrivale says he’s going to explain something before a distraction causes that explanation to be deferred. I suppose it’s one way to explain why the sleuth keeps things close to himself – in this case it’s not for lack of trying, but he really doesn’t try very hard.

“We are going to be married. Whee!”

The one real failing is in the character of Marcia. Not because she and Sanders are one of Carr’s twenty-four hour romances – at least they aren’t cousins in this one – but she does do a couple of things, such as pinching evidence from the crime scene, for no clear reason other than that’s what women do. It’s a shame, as the other primary female character is much more interesting.

All in all, I think this is an overlooked little masterpiece. Yes, the impossible poisoning isn’t great and the impossible disappearance just… isn’t, really, but as a mystery, this is first-rate. Merrivale’s explanation of how he, and the reader, should have spotted the killer makes perfect logical sense. And I guarantee you won’t work it out for yourself. Here’s hoping this sees a reprint one day…

I liked the secondary question of explaining why they have these weird objects on them, as well as the false solutions we get for that. Reminds me of the Arabian Nights Murder, where a big part of the puzzle is explaining why people behaved so oddly, rather than just explain how a crime was committed.

LikeLike

[…] have just finished reading a review of Carter Dickson’s Death in Five Boxes, written by my pal, the Puzzle Doctor, and I must say […]

LikeLike

I think you were fairer than Brad in this one 😁

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just composing my response to his review. While I appreciate the murder does break one of Knox’s rules, the fact is, you can deduce the killer from what is basically a multitude of clues pointing in their direction. Definitely allowable in this case…

LikeLike

👍

LikeLike

[…] have just finished reading a review of Carter Dickson’s Death in Five Boxes, written by my pal, the Puzzle Doctor, and I must say […]

LikeLike

The crime here never feels air tight enough to be considered impossible; no more so than the first murder in Christie’s Three Act Tragedy. Instead, this book is much better read as one of Carr’s confounding crime scenes: see Death Watch, The Eight of Swords, The Arabian Nights Murder, Too Wake the Dead, or The Five False Weapons. Interestingly, that sort of story typically belonged in the world of Dr Fell, with Merrivale picking up the impossibilities (at least during the 1930’s).

The solution to the “impossible” poisoning never crossed my mind, but it was definitely a let down because it’s a concept that doesn’t feel unique these days. Still, I enjoyed the puzzling setup to the crime. It’s a great book, but I’d personally rate all of the stories that I listed above ahead of it, with the exception of The Eight of Swords. It’s very close to Too Wake the Dead.

LikeLike

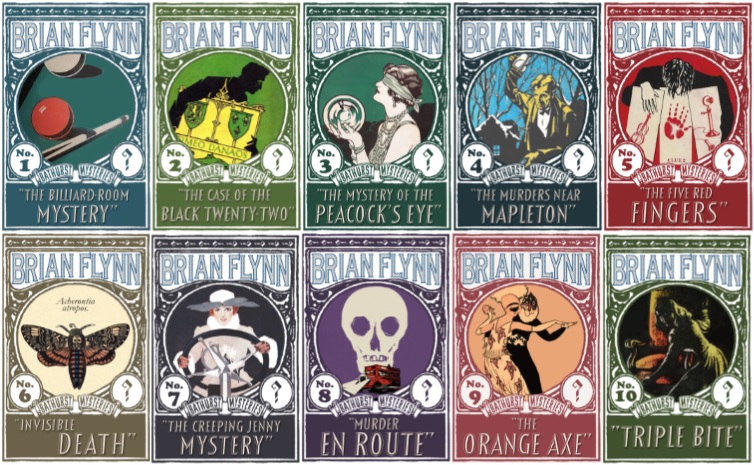

The first cover you’ve used above says that Carter Dickson is unquestionably one of the “big five” – who do people think the other four were?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wonder. Christie, for certain. At this point, were people aware who Dickson really was? So maybe Carr? Crofts?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, yes. As early as The Unicorn Murders. Here’s Nicholas Blake in the Observer (February 1936): “For those who suspect that J. Dickson Carr and Carter Dickson are one and the same writer, more circumstantial evidence is now forthcoming: (1) the growing family likeness between Dr. Fell and Sir Henry Merrivale; (2) the paradoxical opening gambits of the Arabian Nights Murder and the Unicorn Murders; (3) the fact that in both these books the unusual phrase “you overgrown gnome” appears.”

Here’s Ralph Partridge in the New Statesman (also February 1936): “I shall open the innings with the Great Twin Brethren, Messrs. Carter Dickson and Dickson Carr, not only because each can be counted on to knock up so many novels a year, but because in my experience it is quite impossible to separate this pair. If anyone will take the trouble to compare closely the demeanour of Sir Herbert Armstrong in The Arabian Nights Murder and our old friend Sir Henry Merrivale in The Unicorn Murders they might well come to the conclusion that Mr. C.D. and Mr. D.C. are at least identical if not Siamese twins. This literary mystery is more baffling to me than any of those cleared up by Dr. Fell, and I wish he would give his attention to it. Meanwhile, if any of the public have discovered further clues bearing on these authors’ identity or non-identity I should be very pleased if they would communicate with me.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

“An overlooked little masterpiece.” Well said, that man! This is my favourite Carr from 1938; I’ve read it three times, always with satisfaction. The first time I loved the setup – those respectable people with shady secrets – X was an arsonist, Y a pickpocket – and bowled over by the double whammy of the solution: a how that I hadn’t come across, and a who that was cunningly hidden but should have been obvious.

At that time (1998), the only Carr resource online was Grobius Shortling’s site. He liked this one. I was disappointed by The Judas Window (it was meant to be one of his best, but I couldn’t visualise the method, and the murderer wasn’t a huge surprise).

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had the idea that everyone at the time knew Carr and Dickson were the same, but apparently not.

LikeLiked by 2 people

[…] have just finished reading a review of Carter Dickson’s Death in Five Boxes, written by my pal, the Puzzle Doctor, and […]

LikeLike

[…] In Search of the Classic Mystery Novel […]

LikeLike