Edmund Coulston has disappeared. His solicitor and friend, Mr Methwold, is concerned, as Edmund had been staying with him and had not been in a good state of mind. Coulston was concerned that he was being followed by shadowy characters, determined to get their hands on a strange golden idol that he had recently inherited. Searches for Coulston lead to little success, bar for his blood-stained hat – and his leg…

His false leg, that is. But by the time it has been found, Scotland Yard have arrived, in the shape of Inspector Arnold and his friend, Desmond Merrion. The disappearance raises all sorts of questions to perplex Merrion – if somebody killed Coulston, why leave the golden idol, the only apparent motive, to be found? And where is Coulston’s body? And if he lives, where is he? And why has nobody noticed someone who is missing one of his limbs?

I’m not fussed about the condition of the contents of my book collection, provided I can read the book – so I wasn’t fussed when a copy of a Miles Burton (aka John Rhode) book appeared on eBay noting that one of its pages had been replaced with a photocopy. Luckily everyone else who might have bought it did see this as a deal breaker, so I got it for a tenner. Not bad for a title that I don’t recall seeing for sale in recent years…

The war seems to be something of a tipping point for the quality of Rhode/Burton’s work – the pre-1945 stuff is generally stronger than the post-1945 stuff. You could actually use this as the pivot as the preceding The Three Corpse Trick is excellent and the following Early Morning Murder is rubbish. And this one… drumroll… is probably one of the most interestingly structured of the Burton titles.

There is an ongoing to-ing and fro-ing throughout the book as to whether Coulston is alive or not. I thought early on that I was being clever when I had my theory that Coulston had faked his own death, but when Merrion came up with it a few pages later, I figured I was wrong. But unlike a lot of Golden Age plots, this twists and turns all over the place. Is he dead? If not, is he the prime mover in the plot? Is he held prisoner? Rhode/Burton holds his cards close to his chest until very late on, and I’m not going to give anything away, but while I did figure out the final detail (just) before it was revealed, I wasn’t sure what was going on for a very long time, which isn’t that common with the author, especially having already read Early Morning Murder, where he tries something different (with a lot less success than here).

One quick question for those in the know – does it count as breaking the “Chinaman” commandment in Knox’s Decalogue is someone imagines there are being followed by “sinister orientals” when they aren’t any such individuals?

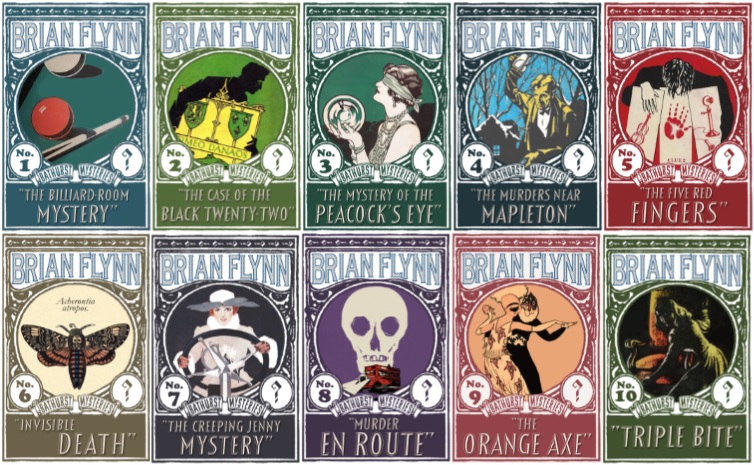

Anyway, definitely one to keep an eye out for – if anyone out there is planning to reprint the Miles Burton titles, please hurry up…

Does it count on breaking the “Chinaman” commandment? Nope, that’s just blatant racism. And before you say “there goes Bradley being flippant,” I’m totally serious. According to Jeffrey Marks, Knox did not write that commandment to prevent stereotyping against Asians; he wrote it because by that time, there were so many Asian villains in mystery fiction but it was a cinch that any Asian character that showed up would be a bad guy! Knox was trying to eliminate easy answers that the reader would guess immediately! Since there are no Asian characters in the Burton book, this is merely an example of the sadly typical early-century fear-response to exotic characters, otherwise known as racism.

LikeLike

In this case, a disturbed character is fearing that such an individual is pursuing him, a thought that is dismissed as sensationalist nonsense by everyone else, so I don’t think this can really count as racism, just a reflection of one character reading too many of the stories that Knox is protesting about.

LikeLike

A “Case of the Golden Idol” you say? Hmm…

This sounds intriguingly tricksy. Definitely one for the TBR, if it ever becomes accessible!

Seems to me like the book does not break the rule, but rather plays with it. Due to the rule, we know the character’s delusions can’t be true.

LikeLike