Avory Hume had told his daughter that he was pleased with her engagement to James Answell, but when Answell is summoned to a meeting with Hume in his study, the man’s attitude seems to have changed. But after accepting a drink from Hume, Answell collapses to the floor.

When he wakes, there is no evidence that he was ever given a drink. The door is bolted on the inside and Hume lies dead on the floor with an arrow in his chest, torn from a display on the wall. It seems an open-and-very-shut case but at the last minute, someone new steps forward for the defense – Sir Henry Merrivale himself. But how was Hume killed and what exactly is a Judas Window?

Quick Quiz:

- Do you like classic mysteries?

- Have you not read The Judas Window yet?

If the answer is “yes” to both those questions, then stop reading this review now and head off to the nearest bookshop, buy this book and then read it. I’m really tempted to leave this review here – that really is all you need to know. The Judas Window is one of the finest locked room mysteries ever written – better, in my opinion, that, say The Hollow Man and thanks to the British Library Crime Classics range, it’s finally available.

But let’s take a look at what makes it such a classic.

First of all, the problem is simple. An innocent man wakes up in a room locked from the inside having apparently stabbed someone. That’s it – that’s the problem the reader has to solve.

Secondly, the solution is drip-fed throughout the book. Why is Hume behaving oddly? We know that by the half-way point. What was the murder weapon? Ditto. How did the murderer get in and out of the room? Well, Merrivale repeated tells us how – hey, it’s the title of the book – but that doesn’t actually help us much. But it’s more than some authors would do. Without the mentions of the Judas Window, the ultimate solution would come out of nowhere, but here it doesn’t seem that way. Yes, it’s very unlikely it would work, no matter how big it was (Aoo-er, Matron!) but Merrivale sells it plausibly.

And thirdly, the trial setting. It’s hardly the only murder mystery with this format, but the trial scenes, unlike in a lot of others, sparkle and make the story feel fresh. Merrivale is on top form, his eccentricities are all there, but not in such a way that he endangers the trial.

I could go on, but this book is just marvellous. Marvellous. Well done, British Library, for getting this to the masses – Nine – And Death Makes Ten should be next on the list, or And So To Murder if you want something a little different, just in case you were wondering.

You’re right to highlight this one. When friends and family ask why I like classic impossible crime fiction, I always use TJW as the quintessential locked room example.

It has much to admire including a tremendous impossibility, a wonderful mid-book reveal, Merrivale at his best in the courtroom without weak attempts at humour, etc. And whilst I don’t believe the culprit would have had the skill to plan and execute the murder, I still found the solution clever.

As I read so many mysteries each year, I am guilty of not always remembering all those books well because they didn’t make much impact on me. The best compliment I can pay TJW is that not only do I remember it in detail, I vividly recall where I was and how I felt when reading it. Highly recommended.

LikeLike

Yup, a complete delight of a book, and such an excellent choice by the BL. Now they need to follow this up with The Reader is Warned, and everyone will be happy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wonder if they’d go there – there’s some very dated terminology describing one character that is used quite a bit iirc

LikeLike

Easy to censor, though. They did a similar thing with The Lost Gallows.

LikeLike

So the note at the beginning about outdated terminology should being included should have “unless it’s really dodgy” included in it.

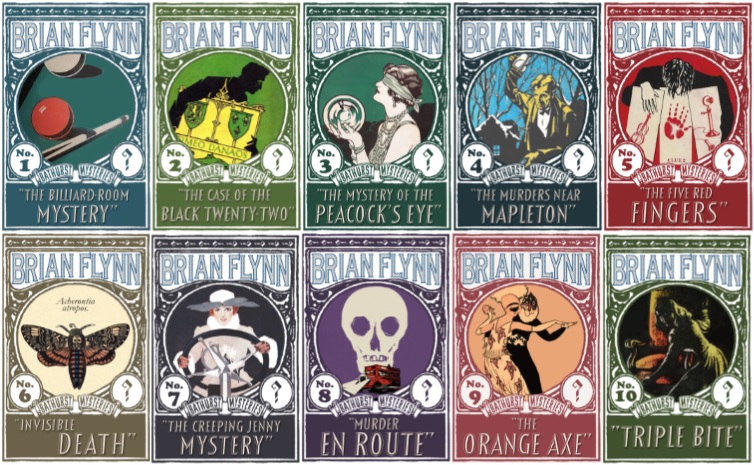

To be fair, we did the same with They Never Came Back by dear old Brian.

LikeLike

The note in the front is often redundant, in fairness, because so few of the books actually have anything in them that’s objectionable. And if those two uses of an offensive terms are what’s presenting TRiW finding a wider audience, well, I’d happily see them expunged for that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Exactly. I know some people are very against the slightest change but I’m not one of them.

LikeLike

I used to be, but I’ve mellowed 🙂

LikeLike